Rotator cuff (RC) injuries are a broad term used to describe injuries of the shoulder that can range from tendinopathy, to partial and complete tears. They are one of the most common soft tissue injuries seen in adults with approximately 30% of adults over the age of 60 suffering from a tear1. But why are they so common? And what can be done to prevent them or alleviate the pain?

Anatomy of the Shoulder

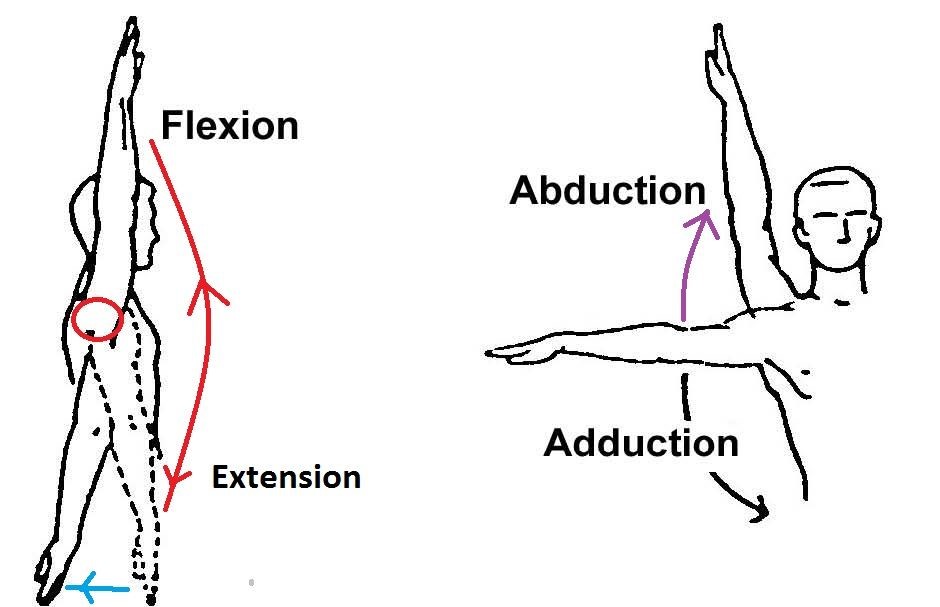

The shoulder is an inherently unstable joint – the large humeral head sits on a relatively shallow fossa and there is a high degree of freedom through flexion/extension, adduction/abduction, internal/external rotation, and circumduction (combination of 3o of freedom). To allow for this large range of motion, passive structures about the shoulder joint (i.e. ligaments) aren’t very stable, so a lot of dynamic stability is “shouldered” (pardon the pun) by the rotator cuff muscles.

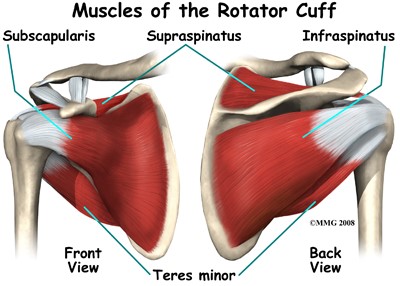

The four muscles of the rotator cuff and their actions are: subscapularis (internal rotation), supraspinatus (initiates abduction), and infraspinatus & teres minor (external rotation)

In addition to these actions, the rotator cuff play an important functional role of providing dynamic stability to the shoulder joint capsule during movement. They work synergistically to prevent unwanted rotation of the humeral head and prevent it from translating forwards, backwards, or upwards.

Causes of Injury & Pain

Shoulder impingement occurs when the head of the humerus compresses the supraspinatus tendon & subacromial bursa. It is typically indicative of RC dysfunction. Studies consistently show weakness and muscular imbalance of the external and internal rotators on the affected side in patients with rotator cuff impingement and shoulder joint instability2. Repetitive arm movements, particularly performed overhead or under high loads, can also cause wear and tear to the RC and may result in injury if the muscles aren’t sufficiently strong to cope with these stresses.

Ensuring a functioning and synergistic RC group and being able to appropriately position and control the scapula during arm movements is vital for preventing common shoulder pathologies. Altered movement or positioning of the scapula is associated with an 8x higher likelihood of experiencing shoulder pain. Similarly, poor posture has been shown to be predictive of RC injuries; with 40-65% of individuals with abnormal postures suffering tears vs. less than 3% with ideal alignment3.

Exercises for Strength & Function

We need to focus on motor control to specifically recruit the RC and muscles that control and position the scapula. This can be through a series of exercises of progressing dynamic movements and loading4. Performing a structured RC strengthening program using therabands and light dumbbells 3 times per week has been shown to successfully improve pain, range of motion, and function in individuals with shoulder pathology5. In general, three sets of 15–20 repetitions are recommended to create a fatigue response and target the development of local muscular endurance.

Motor Control & Scapular Stability

1. Four-point kneeling shoulder flexion – performed with proper motor control without compensatory movements of the scapula or back

2. Standing shoulder flexion, extension, and abduction - RC is used to stabilise and prevent unwanted movements of the humeral head

Specific Strengthening as Movers

Exercises which involve rotation of the humerus (especially external rotation) are commonly used in RC strengthening programs. Maintaining an appropriate strength ratio of 66-75% of external to internal strength is critical since weakness of the teres minor and infraspinatus is a potential cause for shoulder impingement. Programs typically commence with having the arm in a supported position (lying down, or by the side) as in this position the passive structures of the shoulder are providing sufficient support to prevent the humerus moving.

3. Side-lying external rotation - typically first exercise used to elicit high infraspinatus and teres minor activation while minimising strain on the shoulder joint6.

4. Full range shoulder external rotation using exercise band with the upper limb by the side

5. Supine shoulder external & internal rotation with arm abducted to 90o

6. Full range external and internal rotation using a small DB with the arm supported at 90o abduction

As mentioned earlier, the RC have an important function as stabilisers, so we need to train them in that way. We progress the exercises to less stable and more functional upright positions where the shoulder is in a more vulnerable position so the RC is recruited to provide stability.

7. Full range shoulder joint rotation to and from the vertical with upper limb unsupported at 90o shoulder abduction and elbow flexed to 90o. (Can also be performed in prone)